You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Faith’ tag.

There is a lot of uncertainty and chaos in the world at present; this poem may provide some comfort.

Do you need Me?

I am there.

You cannot see Me, yet I am the light you see by.

You cannot hear Me, yet I speak through your voice.

You cannot feel Me, Yet I am the power at work in your hands.

I am at work, though you do not understand My ways.

I am at work, though you do not recognize My works.

I am not strange visions. I am not mysteries.

Only in absolute stillness, beyond self,

Can you know Me as I am,

And then but as a feeling and a faith.

Yet I am there. Yet I am here. Yet I answer.

When you need Me, I am there.

Even if you deny Me, I am there.

Even when you feel most alone, I am there.

Even in your fears, I am there.

Even in your pain, I am there.

I am there when you pray and when you do not pray.

I am in you, and you are in Me.

…….

Though your faith in Me is unsure, My faith in you never wavers,

Because I know you, because I love you.

Beloved I am there.

For the text of the entire poem go to https://www.unity.org/article/i-am-there

On August 7, 1971, the poem “I Am There” was famously carried to the moon by Apollo 15 astronauts James B. Irwin, David R. Scott, and Alfred M. Worden. Stored in a microfilm file, the poem was intended to be left there for future space explorations.

“The problem is that we keep going back to sleep, or otherwise live in ways that neglect this deep knowing. Thus, the crises that we are in the midst of today, whether ecological, political, or societal, stem from the fact that we treat the earth and one another as less than sacred. All these critical issues are interrelated. The way we have wronged the earth is the way we have dishonored the feminine or belittled the “other,” whether that is the “other” nation, religion, race, or sexual orientation. We have fallen out of alignment with the deepest truths within us. How are we to awaken again to the sacredness at the heart of all life, the sacredness that is also at the heart of our own being?

The Celtic spiritual tradition is one that has long emphasized an awareness of the sacred essence of all things. This tradition is in fact part of our Western Christian inheritance, although it has been largely forgotten and at times suppressed…

What is unique about the Celtic tradition compared to most other Western traditions is that it cannot be reduced to a set of doctrines or beliefs; instead, at its core is the conviction that we essentially need to keep listening to what our soul already knows, either in the particular circumstances of our lives or in matters more universal. We need this awareness among us again today, urgently.”

As a child of wonder I felt god in the deep thrum of the church organ, in the soaring notes of the hallelujah chorus.

I felt god in the candle light and smelled god in the incense. I was held by god in the warmth and the dark wood and the solid pews while outside it rained and snowed and the howling wind blew garbage along grey, unkind streets.

I did not see god on the altar in the clothes of my abuser. I did not hear god in the droning of the empty latin words. But when they were sung, ah, then, then my heart soared.

I did not feel god in the dark whispering box or in the hastily recited prayers.

I did not know god when priests claimed my body; they were not searching for god between my legs.

But later, much later, as a teacher on a senior retreat I found god and I cried. I cried because god was crying … for me. Imagine! In the dark of the chapel and outside in the trees god offered the love I craved, father, brother, mother, friend. And the gift broke me. I felt ashamed and unworthy and ran from god.

For years I still sang, of Jesus and God. But it wasn’t my god. For years I intoned the words of the rituals and adapted to the changes. They didn’t mean anything anyway. I baptized my sons and shuddered at the obscenities of the vows made – asking us to reject a mythical demon under threat of everlasting torment – also mythical, and medieval. But it wasn’t my god.

Yet there were tiny slivers of gold to be discovered in the mud and muck on the banks of the river of Catholicism. Matthew Fox worded a truth I already knew in my very being, in my cells: creation was good, good is god, humanity and all the created order are of god and therefore intrinsically blessed. The bible author who scribed Genesis chapter 1 knew it three thousand years ago. But his voice had lost out to the pagan superstitions that found an answer to the problem of suffering and evil in a talking snake and a magic tree. And Augustine, the suffering, morally quaking, self-hating monk of the 4th century found his answer there too. Humanity was banished from Eden to be conceived in pain and suffering and thereby pass on our guilt through the act of procreation. Only the blood-letting of a divine being could undo that banishment.

As a mother I had known organically that my children were conceived in love and goodness and born in purity and goodness and grace. The church had never spoken the truth that resonated somewhere deep in every mother’s womb, like the thrum of a great pipe organ intoning the miracle of conception, life, birth. As Catholic women we knew the doctrine of the fall and original sin. We may have sensed its disordered theology but few of us had the opportunity to study and challenge these doctrines. As a student of theology these doctrines exposed themselves to me as a warped and twisted untruth born of a tortured psyche overwhelmed by his own desires and his own dis-eases of the spirit. Augustine was a great theologian whose mind was infected by the “demon” of self-hatred. And his dis-ease has contaminated Christian the theology of creation and humanity for two thousand years, not just in Catholicism but in the conservative strands of Protestantism too.

Matthew Fox had written the truth. He was a beacon in my spiritual darkness.

Then there was the nature of the Church and the priesthood. The complete contradiction of a theology of the ontological superiority of ordained priests and a systemic approval of pederasty, pedophilia, and the grooming and seduction of vulnerable adults in the Catholic church was enough to make any educated Catholic shudder. So it was important that Catholics remain uneducated in their own theology and history and kept firm in their faith and credulity. But I was educated theologically and experientially: I knew, in a knowing that was intellectual and physical, that the Catholic institution had itself become diseased. Convinced of clergy superiority, the pew Catholics honored, adulated, adored their priests as the presence of god in their community. But what about “in” their son or “in” their daughter? No, that was impossible because priests were of God. The children were lying, they (we) needed to go to confession, be exorcised, be institutionalized. Controlled.

As an educated Catholic, and now as a mother of sons, I was pulled inside out. I could not let my sons grow up unprotected in an unchanged church. I could not defend or support a church that lied every time it was found to be breaking its own rules, its own new and better commitment to protect children. My faith, my career, my intellect, my personal memories all jarred together. I was institutionalized. Numerous times. Eventually my health required a new career. Then another. Searching for meaning still. Trying to get Adam and Eve out of the garden without the specter of the devil, punishment, evil, death.

I wrote out my anger and my pain. I spoke out about the evils of the priest abusers. I went to lawyers and gave testimony. And each time I reached out I was broken again, hospitalized again, overwhelmed and flattened. Time passed. I lost my faith in Catholicism. I lost my oldest son. I lost my god.

I don’t know that time heals exactly but the pain of suffering and loss become more dulled and good memories soften the edges of daily remembering.

I rediscovered Matthew Fox recently. And I rediscovered Pelagius, an early church theologian from Britain who challenged Augustine back in the 4th century. Pelagius and Celtic Christianity had always taught the truth of Genesis chapter 1, “and God saw that it was GOOD.” Pelagius was condemned as a heretic for his troubles. But there are more theologians now who are writing and speaking about original blessing. More women who are challenging the traditional misogynistic theologies and bringing to light the voices of women who have been condemned, silenced, or simply ignored. Women like Mary Magdalene, the first prophet/witness of the resurrection of Jesus. Women like Julian of Norwich, Hildegarde of Bingen, Mother Teresa of Calcutta. And the hundreds yet untranslated, unnamed voices whose message is that all creation and humanity in particular is of god, of goodness, and is a blessing.

Perhaps it is time to write again.

There are many ministers who preach the Prosperity Gospel and many versions of it. But basically it is the view that God intends for good people to be successful, wealthy, and healthy. All you have to do is ask God, even demand it – and give money to the preacher as a sign of your faith. There is an emphasis on healing, yes, but it is usually tied to money ultimately. And typical of evangelical Protestant churches the emphasis is giving money to the minister personally rather than the church organization. A true cult of personality is typical in these churches.

The reverse of the Prosperity Gospel teaching is that if you are poor or ill you must be a sinner and/or not have enough faith. You are a failure and God is not blessing you. Very Old Testament! But, newsflash, Jesus didn’t preach or teach a “prosperity” message.

Jesus would be judged to be a complete failure by the Prosperity Gospel standards. He was poor, he didn’t ask for money, he not only accepted the destitute, the sick, and the sinners, he blessed them – with compassion, some bread and fish, a healing or two, but not with social success and power, and not with gold and jewels.

Jesus did not achieve worldly success, he did not value ostentation, often requesting that people not talk about his healings. He did not crave the limelight but often took time away from the crowds. He wore ordinary sandals and occasionally rode a donkey. He camped out. How can he be compared to the private jet, stretch limo, multi-million dollar mansions type of minister.

Yet these contemporary, evangelical, charismatic, Prosperity Gospel ministers continue to claim to be speaking and acting and living in his name. They must have a different New Testament from mine. Or perhaps they’ve just confused Jesus and King Solomon.

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prosperity_theology

https://www.beliefnet.com/faiths/christianity/8-richest-pastors-in-america.aspx

How do I process my grief?

Does suffering have any meaning?

Do we live in a random chaotic universe?

Is it time to re-evaluate my understanding of “God”?

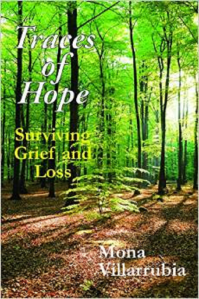

This book is for anyone who has suffered a loss – of safety, of one’s home, of health, of a loved one or a relationship, or of one’s faith … and found themselves asking, “Why?” And then wondering, “Who am I asking?” and hoping they were not alone.

Over the past few years I have used the opportunity offered by this blog to reflect on many questions about Catholicism – my faith home. Along the way I have left my career as a Catholic religious educator and more recently I have left my home in the Catholic Church for a new faith community in the United Church of Christ. It would be inappropriate to continue to comment on the Catholic Church as if I were a member, and so I will be changing the blog’s name to Christianity in the 21st Century.

I have a new book coming out that tells the story of my faith journey and my journey through grief and loss, if you are interested in my full story.

A Mother – protecting her children (the membership) from historical truth and theological insight, and the responsibilities of independent thought. Trying desperately to keep her babes from leaving the nest.

A Lioness – protecting her cubs (the clergy) by hiding them from attack, redirecting attention away from them, retaliating against their attackers.

A “Uriah Heep” – whose only concern is to protect and gain control over the moneys taken in by the business. Motivated by greed, and putting on a face of insincere humility.

A model of the Church of “Bishop” Francis? – I remain hopeful.

A friend died yesterday. Death is always an event that raises existential questions. And so I have been thinking about God and meaning and I wonder if perhaps the reason we need to believe in a God is not so much that we need to believe in an all powerful creator, and a grand design and purpose for the universe, but rather that we simply want to believe in “I.” We want the Self that we experience to be a reality, and, for that to be true, our Self has to be important to someone or something beyond ourselves. We don’t want to believe that we are just an anonymous part of a chaotic universe in which neither the universe or our Self has a purposeful beginning, history, or future. We don’t want to believe that our actions and reactions are just a matter of chemicals and neurological responses. We want to believe in the I, the Self, and the power of free will. For our individual Self to be real, we have to believe that there is something intrinsically different, ontologically different, between our species and other species: our ability to create ideas from nothing, not just imitate; our ability to love selflessly; our ability to recognize and respond to the Divine. And so we are drawn to the notion of a God who created it all from nothing, the universal Thou to our personal I. A Being who created us, chose us, knows us, loves us – and not just us collectively but individually.

I attended synagogue services Friday evening and prayed for my friend’s recovery. But I find the Reform Jewish service unsatisfying. It identifies the concept of a God, a creator, the name above all names, but without a re-enactment, without God’s words being spoken directly to us in some ritual drama, we never quite cross the threshhold of an invitation to believe in God and move into an engagement in communication with God.

In a Christian eucharist the words and acts of Jesus at the last supper (in so far as Paul remembers them) are re-enacted. We enter into that drama through our responses, and we participate, allbeit in a theatrical fashion, in a relationship with a God who knows us and loves us – each of us individually in our very Self – loves us enough to die for us. There is great power in this experience. It can bring about changes in a person’s life, elicit a decision to pursue a vocation, bring about conversion, provide relief from despair. It doesn’t matter who takes the role of Jesus, there is no magical power bestowed at ordination and no significance to gender, what is important is that someone speaks in Jesus’ place, addressing us in the first person, and that that someone believes in what they are saying. If you like, they have to be a good actor. If you love live theatre and live music as much as I do you will know the power of a good performance: for a while you can be completely drawn in to an alternate reality. The Eucharist is live drama and at it’s best it has the power to draw us in to an alternative reality to the one presented by society. And what it teaches us is that this alternative reality – a God centered universe – is the Truth.

Love relationships have a similar power to affirm the Self. We are known and chosen by another, our Self becomes more real because someone else acknowledges it. One level of devastation in a break-up is the loss of that sense of Self, our I. Without someone to love us how do we know who we are? Or even if we really exist. People will even comment, She seems lost.

It is common knowledge by now the degree of damage done to an infant that does not have its existence affirmed, that does not bond to a caretaker, that does not experience loving eyes and touch – statistically they have a harder time simply staying alive, and certainly they will struggle to thrive. But that need does not end in infancy. Without the love of parents and close friends and partners and children to identify us, who are we? If we at least have faith in a God, we have a chance of believing in our reality, our existence as an I, a separate Self. But without belief in the love of God and without the love of intimate relationships? It is easy to understand the descent into hopelessness and despair of the isolated and depressed individual who faces a world in which he seems to be invisible.

Does technology help here? I don’t think so. People do not encounter us as who we are through social media, so our identity, our I, is not affirmed. There are layers upon layers of deception and secrecy on the internet that we use to shield ourselves from others. So it does not really help in our quest to affirm out existence, our identity, our uniqueness. Encountering our true Self requires real interaction in person with another, and seeing and experienceing their acceptance of us as an I that exists and is unique and worth knowing.

My friend was with my husband and me for four months in Houston after Katrina, part of an uprooted high school community from New Orleans. We all became friends and I discovered in him a brooding, anxious, angry side that made me afraid for him. But after Katrina he married and had a baby. He was more mellow, his existence had been affirmed, his identity had been acknowledged: he had been singled out and chosen above all others. There was less anger, more real joy. I’m so glad he had that experience – of being (re)created, of his Self being affirmed – before he died at the young age of 39. And if there is a God, my friend will now know for certain who he is and how much he is loved.

“…biblical authors often used humor and the absurd to alert their readers that something very important is about to happen. The births of Isaac and Jesus were my two examples. The idea that either a woman in her nineties or a virgin can give birth is, I said, absurd, and the authors knew this to be so. They never expected their readers to take them literally. Rather they were saying, look these births herald the coming [of] something new into the world and hence break with the normative ways of producing offspring.” Rabbi Rami Shapiro, http://rabbirami.blogspot.com/2012/11/stand-up-theology.html

We all love Thanksgiving dinner and all its trimmings – a beautiful family tradition that brings our families together and mends and heals and nurtures. Now, just a few weeks later we are immersed in the Christmas story and all its trimmings. And, once again, we prepare for family gatherings and for opportunities to renew and reclaim, to nest and remember. But what is it as Christians that we are called to remember? What is the Christian heart of our Christmas story?

Obviously, it’s not Christmas lights and fir trees; it’s not snow men or reindeer. It’s not Santa Claus or even Saint Nicholas – he came much later.

Is it the angels singing in the fields, and the shepherds? Is it wise men from the East and their gifts? Is it Herod’s slaughter of the innocents – that’s hardly festive? Okay, what about the stable and the ox and ass and manger? There has to be a manger because of the song, right? And everybody loves the scene of the angels and shepherd and the baby!

Everybody loves a story of a baby, especially one in which there is danger and pathos and heroism and compassion and beauty and a happy ending with angels singing and a star from heaven guiding a family to safety so a baby can be born under a starry sky….ahhhh! Cue the heavenly chorus. Then add the mysteries and treasures of the Orient and a baby lamb and some portentous dreams. What is not to like about this story? But we still haven’t gotten to the Christian heart of the story. We are still in the Christmas Story. And that is where Christmas stays for so many people it seems, and not just children.

In my experience, adult Christians who have become disenchanted with Christmas have become disenchanted with the Christmas Story not with the Christian Story. In fact they may not really know the Christian story. And here we get to Rabbi Rami’s point. The Gospel writers, writing decades after Jesus’ death, were not historians of his life; they were not biographers. They were tellers of his Teaching, Death, and Resurrection – and only as an afterthought his birth, and only because, after all, he had to have had one. In telling about his birth their main concern was to say that God was involved, and that from the very beginning the Jesus Event was a God Event. Not just from the moment of his baptism (Mark), not just from the moment of his announced conception (Matthew and Luke) but even from before the moment of creation (John).

The Gospel writers, when addressing the issue of Jesus’ birth, were giving us theology not biology. They weren’t interested in eggs, sperm, uteruses – they didn’t know about such things. They weren’t interested in the human person as evil matter versus a good spirit, that idea was a Greek idea that didn’t have any influence on the Gospel writing, obviously, because Jesus clearly had a body in all the Gospel narratives. The Gospel writers weren’t concerned about Original Sin either; Augustine would create that idea a few hundred years later.

The Gospel writers were telling us, using hyperbole and using Old Testament allusions, that the Jesus Event was a God Event, and that it had always been a God Event, since the beginning of Jesus’ life, or even since the beginning of all time. Moreover, the Jesus Event had been prefigured by many different stories in the Old Testament, showing that Jesus was indeed the true Messiah of Jewish expectation. For example, Micah prophesied the Messiah would be born in Bethlehem.

The author of the Gospel of Matthew especially took great pains to connect his version of the Infancy Narrative, as it is called, to prophecies in the Old Testament. For example he connects the family’s trip to Egypt, and the ensuing slaughter of the innocents – two stories no other Gospel includes – to prophecies in Hosea and Jeremiah respectively. It is generally agreed that Matthew’s audience was primarily Jewish-Christian and in his use of Old Testament quotes and allusions he may simply be using a literary device to make his theological points: the Jesus Event was a God Event; Jesus was indeed the Jewish Messiah. The early Christians hadn’t gone any further than this in trying to figure out Jesus’ relationship to God yet, other than the basic language of Father, Son, and Spirit. The debate about the Trinity took nearly four hundred more years to settle (Council of Nicea 325, Chalcedon 451).

So what then is my point? If we are suffering from Christmas ennui, maybe it’s because we simply have lost sight of the Christian Story. My solution? Let’s give ourselves the gift of a LITERARY GOSPEL CHRISTMAS. Let’s do some reading of the Gospel narratives with a footnoted Bible translation and/or scholarly commentary at hand and really attempt to understand the Christian Story beneath the Christmas story before we call Bah Humbug to it all!

Fellow Travelers? Four Atheists Who Don’t Hate Religion

Paul J. Griffiths, Commonweal Magazine, October 26, 2012

My Comment in response to his article:

Paul, I want to thank you for providing such an informed review of the apologists for the Church without Christ (and the Synagogue without Yahweh).

To put it more bluntly, the secular self-understanding of the liberal state can no longer motivate its citizens to act self-sacrificially in the service of justice. Its failure to find a way to mark death is mirrored by its failure to make passionate collective action a real possibility.

I am currently ambivalent about God, but find myself longing for a Catholic faith community without the Church. What the Catholic Church has come to represent to me is not God but human corruption, self-serving arrogance, and power-hungry pope mongers. The answer is not to give up on God but on the structures of power that inhibit the values of love and self-sacrifice, beauty and reverence, honesty and penitence from becoming present and visible to the Catholic community. The Catholic faithful need to take ownership of these values, take responsibility for their understanding of the message of Jesus, and take over the practice of faithful witness.

I don’t want any priest at my funeral. I may want a particular priest friend of mine, or perhaps a Rabbi – also a dear friend, because each of these friends exemplifies the values of compassion, tenderness, integrity, and justice rooted in a life of reflective, religious faith that I recognize as truly “of God.”

As a victim of sexual abuse by Catholic priests, one of five in my immediate family, the worst way to mark my death for my family would be with an anonymous representative of the organization responsible for our suffering. Even an empty Church would be painful – the context of our abuse. But what about a house with a gathering of loved ones, and the Catholic prayers and rituals of a funeral rite led by those present? There could be priests, rabbis, druids, agnostics, atheists, as long as each one was a friend representing only his or her own faith in God and/or love of me.

Perhaps one thing of value that can come from the sexual abuse crisis in our Church is that it might make “passionate, collective action a real possibility” among Catholics who are still faith-travelers in search of God, Love, Truth, and Justice. Then maybe more of us can forestall the rejection of God that would bring us, finally, to that empty church and a memorial with no blessing.